Charles L. Grant - The Pet

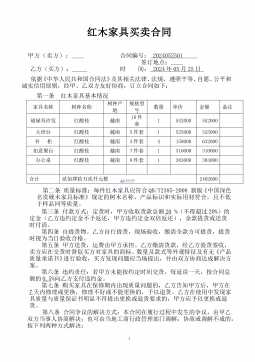

VIP免费

2024-12-24

3

0

473.73KB

232 页

5.9玖币

侵权投诉

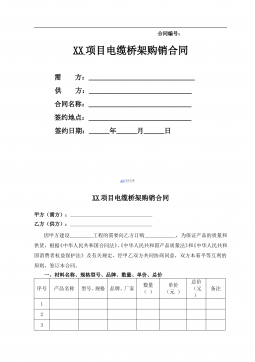

THE PET

CHARLES L. GRANT

i

"An exciting and well-written horror story. ... A brilliant and furious

tale ... as skillful as the whisper of the surgeon's blade."

-Whitley Strieber, author of Catmagic

The water lying on the sagging brick walk was clear and unrippled, and

along one edge was a shadow that was neither the tree in the yard nor

the eaves nor himself crossing over.

The shadow didn't move.

It suggested something much larger, much darker, than he had first

imagined, but when he examined the sidewalk, the yard, the stoop behind

him, he saw nothing.

The shadow was still there, and when he kicked at the water to rough it,

it remained unmoved.

He stamped a foot into the puddle and watched the shadow slip over his toes.

The shoe yanked back and he looked up quickly, then sighed his relief

aloud. A cloud. It was a black patch of cloud. Nothing more.

He had his hand on the doorknob when he heard the noise behind him.

Soft. Hollow. Slightly uneven, stones dropping lightly onto a damp

hollow log.

It was coming up the walk. ...

ii Look for these Tor books by Charles L. Grant

AFTER MIDNIGHT (editor)

GREYSTONE BAY (editor)

THE HOUR OF THE OXRUN DEAD

MIDNIGHT (editor)

NIGHTMARE SEASONS

THE ORCHARD

THE PET

iii

THE PET

Charles L Grant

A TOM DOHERTY ASSOCIATES BOOK

iv

This is a work of fiction. All the characters and events portrayed in

this book are fictional, and any resemblance to real people or incidents

is purely coincidental.

THE PET

Copyright ©1986 by Charles L. Grant

All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this book or

portions thereof in any form.

First printing: June 1986

First mass market printing: May 1987

A TOR Book

Published by Tom Doherty Associates, Inc.

49 West 24 Street New York, N.Y. 10010

ISBN: 0-812-51848-9 CAN. ED.: 0-812-51849-7

Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 85-52254

Printed in the United States of America

0987654321

v

For Kathryn. Because.

vi

CHARLES L. GRANT

1

ONE

A cool night in late September, a Wednesday, and clear- the moon pocked

with grey shadows, and a scattering of stars too bright to be masked by

the lights scattered below; the chilled breath of a faint wind that

gusted now and then, carrying echoes of nightsounds born in the trees,

pushing dead leaves in the gutters, rolling acorns in the eaves,

snapping hands and faces with a grim promise of winter.

A cool night in late September, a Wednesday, and dark.

... and so the boy, who really wasn't a bad kid but nobody really knew

that because of all the things he had done, he looked up in the tree ...

And from the Hudson River to a point midway across New Jersey, the land

climbed in easy steps toward the Appalachian chain. The forests were

gone and so were most of the pastures, replaced by communities that grew

in quick time into small towns and small cities, pieces of a jigsaw fit

too close together.

One piece was Ashford, a piece not the largest, settled on

2

the first of those low curving plateaus, its drop facing south, low

hills at its back. From the air it was indistinguishable from any of its

neighbors-just a concentration of lights, glints on the edge of a long

ebony razor.

... and he saw the crow sitting on the highest branch in the biggest

tree in the world. A big crow. The biggest crow he had ever seen in his

life. And the boy knew, he really and truly knew, that the crow was

going to be the only friend he had left in the world. So he talked to

the crow and he said ...

The park was in the exact center of town, five blocks deep and three

long blocks wide, surrounded by a four-foot stone wall with a concrete

cap worn down in places by the people who sat there to watch the traffic

go by. At the north end was a small playing field with a portable

bandstand erected now behind home plate, illuminated by a half-dozen

spotlights aimed at it from the sides; and the folding chairs, the lawn

chairs, the tartan blankets and light autumn jackets covered the

infield, protecting the large audience from the dust of the basepaths

and the spiked dying grass slowly fading to brown.

A student-painted banner fluttered and billowed over the handstand's

domed peak, unreadable now that twilight had gone, but everyone knew it

proclaimed with some flair the approach of Ashford Day in just over a

month. The concert was a free preview of the events scheduled for the

week-long celebration-a century-and-a-half and still going strong.

The high school band members sat on their chairs, wore their red

uniforms with the black and gold piping, and played as if they were

auditioning to lead the Rose Bowl parade. They slipped through "Bolero"

as if they knew what it meant, marched through Sousa as if they'd met

him in person, and they put fireworks and rockets, Catherine wheels and

Roman candles exploding and spinning into the

3

audience's imagination, into the dark autumn sky, when they bellowed and

strutted through the "1812 Overture."

At the rim of the field, back in the bushes where the lights didn't

reach, there were a few giggles, a few slaps, more than a few cans of

beer popping open.

... do you think it'll be all right?

The parents, all the relatives, the school board, and the mayor

applauded as if they'd never heard anything quite so grand in their lives.

The bandmaster beamed, and the band took a bow. There were no encores

planned, but the applause continued just the same.

... and the crow said, it'll be just fine as long as you know who your

friends really are.

In the middle of the park was an oval pond twenty feet wide, with a

concrete apron that slanted down toward the water. It wasn't very deep;

a two-year-old child could wade safely across it, but it reflected

enough of the sun, enough of the sky, more than enough of the

surrounding foliage to make it seem as if the depths of an ocean were

captured below the surface. Around it were redwood benches bolted to the

apron's outer rim. Above them were globes of pale white atop six bronze

pillars gone green with age and weather. Their light was soft, falling

in soft cowls over the quiet cold water, over the benches, over the

eleven silent children who were sitting on them now. They didn't listen

to the music, though it was audible through the trees; they ignored

applause that sounded like gunshots in the distance; instead, they

listened to the young man in pressed black denim who crouched at the

apron's lip, back to the pond, hands clasped between his knees.

4

His voice was low, rasping, his eyes narrowed as he sought to draw the

children deeper into the story.

"And so the boy said, how do I know who my real friends are? Everyone

hates me, they think I'm some kind of terrible monster. And the crow, he

laughed like a crazy man and said, you'll know them when you see them.

The boy was a little afraid. Am I a monster, he asked after a while, and

the crow didn't answer. Are you one of my friends, the little boy asked.

Of course I am, said the crow. In fact, I'm your best friend in the

whole wide world."

The children stirred as the applause faded, and they could hear the

first of the grown-ups drifting down the central path. The young man

frowned briefly. He thought he had planned the story better, to end just

as the band did, but he had gotten too carried away, elaborating and

posturing to get the kids laughing so they wouldn't be bored. Now he had

lost them. He could see it in their eyes, in the shifting on the

benches, in the way their heads turned slightly, too polite to ignore

him outright though their gazes were drawn to the blacktopped walk that

came out of the dark on its way to the south exit.

"Crows don't talk," one ski-capped boy suddenly declared with a

know-it-all smile as he slipped off his seat.

"Sure they do," a girl in a puffy jacket argued.

"Oh, yeah? You ever hear one, smarty?"

"Bet you never even saw one, Cheryl," another boy said. "I'll bet you

don't even know what they look like."

The girl turned, hands outstretched. "Donald, I do so know what one

looks like."

The others were lost now, noisily lining up as if choosing sides for a

game. The crow's supporters were outnumbered, but they made up for it

with indignant gestures and shrill protests, while the mocking

opposition-mostly boys, mostly the older ones-sneered knowingly and

laughed and punched each other's arms.

5

"Everyone knows what a crow looks like," Don said, in such a harshly

quiet way that they all turned to look. "And everyone knows what the

biggest crow in the world looks like, right?"

A few heads instantly nodded. The rest were unconvinced.

Don smiled as evilly as he could, and stood, and pointed to the nearest

tree, directly behind them. Most of them looked with him; the others,

sensing a trick and not wanting to give him the satisfaction, resisted.

Until the little girl put a hand to her mouth, and gasped.

"That's right." He kept pointing. "See? Right there, just out of the

light? Look real hard now. Real hard and you won't miss it. You can see

his feathers kind of all black and shiny. And his beak, right there by

that leaf, it's sort of gold and pointed like a dagger, right?"

The little girl nodded slowly. No one else moved.

"And his eyes! Look at them, they're red. If you look real hard-but

don't say anything or you'll scare him away-you can see one just over

there. See it? That little bit of red up in the air? It looks like

blood, doesn't it. Like a raindrop of blood hanging up there in the air."

They stared.

They backed away.

It was quiet in the park now, except for the leaves.

"Aw, you're fulla crap," the ski-capped boy said, and walked off in a

hurry, just in time to greet his parents strolling down from the

concert. He laughed and hugged them tightly, and Don without moving

seemed to stand to one side while the children broke apart and the oval

filled with voices, with feet, with faces he knew that thanked him for

watching the little ones who would have been bored stiff listening to

the music, and it was certainly cheaper than hiring a sitter.

He slipped his hands into his jeans pockets and rolled his shoulder

under the black denim jacket and grey sweatshirt.

6

His light brown hair fell in strands over his forehead, curled back of

his ears, curled up at the nape. He was slender, not tall, his face

almost but not quite touched by a line here and there that made him

appear somewhat older than he was.

Within moments the parents and their children were gone.

"Hey, Boyd, playing Story Hour again?"

He looked across the pond and grinned self-consciously. Three boys

walked around the pond toward him, grinned back, and roughed him a bit

when they joined him, then pushed him in their midst and herded him

laughing toward the bike stand just inside the south gate.

"You should've been there, Donny," Fleet Robinson told him, leaning

close with a freckled hand on Don's arm. "Chris Snowden was there." He

rolled his eyes heavenward as the other boys whistled. "God, how she can

see that keyboard with those gazongas is a miracle."

"Hey, you'd better not say stuff like that in front of Donny the Duck,"

said Brian Pratt solemnly. Then he winked broadly, and not kindly. "You

know he doesn't believe in that kind of talk. It's sexist, don't you

guys know that? It's demeaning to the broads who jerk him off on the porch."

"Drop dead, Brian," Don said quietly.

Pratt ignored him. With a sharp slap to Robinson's side he jumped ahead

of the others and walked arrogantly backward, his cut-off T-shirt and

soccer shorts both an electric red and defiant of the night's early

autumn chill. "But if you want to talk about gazongas, you crude

bastards, if you're really gonna get down in the gutter, then let me

tell you about Trace tonight. Christ! I mean, you want to talk excellent

development? Jesus, I could smother, you know what I mean? And she was

waiting for it, just waiting for it, y'know? I mean, you could see it in

her eyes! Christ, she was fucking asking for it right there on the

stage! Oh, my god, I wish to hell her old man wasn't there, he should've

been on duty or

7

something. Soon as she put down that stupid flute I'd've planked her so

damned fast ... oh god, I think I'm dying!"

Robinson's hand tightened when he felt the muscle beneath it tense.

"Don't listen to him, Don. In the first place, Tracey hasn't talked to

him since the first day of kindergarten except to tell him to get the

hell out of her way, and in the second place, he don't know nothing he

don't see in a magazine."

"Magazine, shit," scoffed Jeff Lichter. "The man can't even read, for

god's sake."

"Read?" Pratt said, wide-eyed. "What the hell's that?"

"Reading," explained Tar Boston, "is what you do when you open a book."

He paused and put his hands on his hips. "You remember books, Brian.

They're those things you got growing mold on in your locker."

Pratt sneered and lifted his middle finger. Robinson and Boston, both

heavy set and both wearing football jackets over light sweaters, took

off after him, hollering, windmilling their arms as though they were

plummeting down a hill.

Ahead was the south gate, and beyond it the lights of Parkside Boulevard.

Jeff stayed behind. He was the shortest of the group, and the only one

wearing glasses, his brown hair reaching almost to his shoulders. "Nice

guys."

Don shrugged. "Okay, I guess."

They walked from dark to light to dark again as the lampposts marked the

edge of the pathway. Jeffs tapped heels smacked on the pavement; Don's

sneakers sounded solid, as if they were made of hard rubber.

"How'd you get stuck with that?" Lichter asked with a jerk of his thumb

over his shoulder.

"What, the story stuff?"

"Yeah."

"I didn't get stuck with it. Mrs. Klass asked me if I'd watch Cheryl for

a while. Said she'd give me a couple of

8

bucks to keep her out of her hair. Next thing I knew I had a gang."

"Yeah, story of your life, I think."

Don looked but saw nothing on his friend's face to indicate sarcasm, or

pity.

"She pay you?"

"I'll get it tomorrow, at school."

"Like I said-story of your life."

At the bike stand they paused, staring through the high stone pillars to

the empty street beyond. Pratt and the others were gone, and there was

little traffic left to break the park's silence.

"That creep got away with another one, you know," Jeff said then,

looking nervously back over his shoulder at the trees. "The Howler, I mean."

"I heard." He didn't want to talk about it. He didn't want to talk about

some nut over in New York who went around tearing up kids with his bare

hands and howling like a wolf when he was done. Five or six by now, he

thought; once a month since last spring, and now it was five or six

dead. And the worst part was, nobody even knew what he looked like. He

could be an old man, or a woman who hates kids, or ... or even a kid.

"Well, if he comes here," Lichter said, glaring menacingly at the

shadows, his hair wind-fanned over his eyes, "I'll kick his balls right

up to his teeth. Or get Tracey's old man to arrest him for unlawful

mutilation."

Don laughed. "What? You mean there's such a thing as lawful mutilation?"

"Sure. Ain't you never seen the dumb clothes Chris wears? Like she was a

nun sometimes? That's mutilation, brother, and she ought to be arrested

for it."

They laughed quietly, shaking their heads, sharing the common belief

that Chris Snowden's figure was more explosive than dynamite, more

powerful than a speeding bullet,

9

more likely to cause heart attacks in every senior class male than

failing to make graduation.

Lichter took off his glasses and polished them on his jacket. "I'll tell

you, she's enough to make me wish I was a virgin again."

This time Don's laugh was strained, but he nodded just the same. He

wasn't a prude; he didn't mind talk about sex and women, but he wished

the other guys would quit their damned bragging, or their lying. If they

kept it up, one of these days he was going to slip and get found out.

"So, you start studying for the bio test next week?" Lichter asked, his

sly tone indicating he already knew the answer.

"Yeah, a little," he admitted with an embarrassed grin. "Should be a snap."

"Right. A snap. And if it isn't, you and I will be standing outside when

graduation comes around," He sighed loudly and looked up at the stars.

"Oh, god, only eight more months and the torture is over."

The wind kicked up dust and made them turn their heads away.

"School," Jeff said then, with a slap to his arm.

"Yeah. School."

Lichter nodded, left waving at a slow trot, veering sharply right and

vanishing. Don knelt to work the combination of the lock he had placed

on the tire chain, then straddled the seat and gripped the arched

handlebars. They were upright, cranked out of their racing position less

than ten minutes after he had brought it home from the store. He didn't

like hunching over, feeling somehow out of control and forever toppling

unless he could straighten his back. He pushed off, then stopped as soon

as he was on the sidewalk. To the right, far down the street, were the

hazed neon lights of Ashford's long shopping district; directly opposite

was the narrow island of trees and grass that separated the wide

boulevard into its east

10

and west lanes; to the left the street poked into a large residential

area whose houses began as clean brick and tidy clapboard and eventually

deteriorated into rundown brownstone and aluminum siding that had long

since faded past its guarantee.

He glanced behind him and smiled suddenly.

On the path, just this side of the last lamppost, was a feather. A

crow's feather twice as long as a grown man's hand. It shimmered almost

blue, was caught by the wind, and tumbled toward him.

He waited until it fluttered to a stop against the bike's rear tire,

then shook his head slowly. Boy, he thought, where were you when that

kid opened his big mouth?

But as Jeff would say-the story of his life. Honest to god giant crows

were not in his stars.

Tanker Falwick swore impotently under his breath. Thorns in the

red-leafed bush had snagged his coat sleeve and held it fast, and he

couldn't move quickly without making a hell of a racket. He slapped at

them angrily while he rose and peered over the wall. And groaned with a

punch to his leg when he saw his last chance for decent prey getting

away. The boy was turning, bumping his ten-speed down off the curb and

across the street. Away from the park, in spite-of the moon.

It was too late. Goddamn, it was too late.

"Shit!" he said aloud, and yanked his arm until the thorns came loose.

"Fucking shit!"

A glance up at the moon riding over the trees, and he swore again,

silently, hoping that the squirrel he'd killed earlier wouldn't be the

only meal he'd have tonight. There hadn't been much meat and its heart

had been too small, and twisting off its head didn't give him near the

same satisfaction as tearing out a kid's throat.

Several automobiles sped past, a half-empty bus, a pickup with three

punks huddled and singing in the bed, a dozen

11

more cars. None of them stopped, and when he headed back into the trees,

he couldn't hear a thing, except his paperstuffed shoes scuffling

wearily through the leaves. He hushed himself a couple of times before

finally giving up. He wasn't listening, and there was, most likely, no

one else around to hear.

The whole place had just been filled with damned kids, just filled to

the rafters with them, and every opportunity he'd had to introduce

himself to one had been thwarted in one way or another.

A large dirt-smeared hand wiped harshly over his mouth, not feeling the

stiff greying bristles on his chin, on his sallow cheeks, on the slope

of his wattled neck. He sniffed, and coughed, and spat into the dark.

Then he drew his worn tweed jacket over his broad chest, hunched

powerful shoulders against the wind, and moved toward the center path.

He waited in the shadows for a full five minutes, then stepped out and

took a deep breath.

He didn't like it back in there. He didn't like it at all despite his

affinity with the best parts of the dark. There were too many noises he

didn't understand, and too many shadows that trailed after him as he

trailed the children who were scurrying after their parents.

A lousy night, all in all-except for the music.

He stopped at the oval pond, checked the path, and knelt on the apron,

then leaned over and scooped some of the cold water into his mouth.

The music was nice. Not bad for a bunch of fucking dumbass high school

kids, and he had even recognized some of the tunes. He had been hiding

behind a patch of dense laurel just to the left of the bandstand,

nodding, humming silently, and applauding without sound at the end of

each number. He had also been hoping that one of the punks would have to

take a leak during the program and wouldn't be prissy about heading into

the bushes. Tonight he wasn't fussy

12

about the sex; one of the boys would have done just as nicely as one of

them young whores.

When that didn't work and he couldn't move anyone over to him through

the sheer force of his will, he had moved down toward the south entrance

since that's where the fewest of the audience had headed when it was

over. He was hoping for a stray, but the little ones were too good, too

well-behaved, like those who were at the pond while that other kid, the

older one, the punk bastard in black denim, told them a preposterous

story about a stupid giant crow.

And the big ones, the punks, the snot-nosed creeps who made up most of

his fun, they stuck together like glue right to the street. Especially

the whores.

He rocked back on his heels and dried his face with a sleeve.

That had been a close one, that one had, the moment with the black

denims. Suddenly the punk had pointed right to the tree where he had

been concealed, and he thought for sure he'd been caught, the cops would

be on his ass, and he'd be fried without a trial. Then the kid had

jabbered on about this dumb creature of his, and there was an argument,

and Tanker was able to slip away without detection.

That, he thought smugly, was the easy part-because he was a werewolf.

The realization of his condition had been a long time coming, starting

shortly after he had been handed his separation pay and papers. They

said he had lost his touch with the new recruits; they said he wasn't

living up to the image of the "new army"; they said he drank too much;

they said it was against the new rules to hit the little snots when they

didn't obey his commands. They said. They, who weren't hardly born when

he had first signed his name in that pissant office in Hartford. And

they said he ought to be able to find a pretty good job somewhere, that

his pension and the job would take

13

care of him for the rest of his life. After thirty years, though, the

rest of his life wasn't all that far away.

He left Fort Gordon, Georgia, as he had arrived-on foot, his belongings

slung over his shoulder. Refusing several offers of a ride, he walked

into Augusta, put his things into a locker at the bus station, then went

out and beat the shit out of the first kid under twenty he could find.

There had been a full moon that night, and though a number of people saw

and chased him, he had escaped. He noticed the connection right away

because he had been running ahead and behind his shadows the whole time,

and he decided then and there that the moon would be his charm. It would

help him in civilian life make a fortune and spit on those young

bastards who thought they knew what the military was all about.

It didn't, though. It had plans for him he hadn't known at the time.

As winter passed, and the jobs passed, and he was constantly in trouble

for mouthing off to spineless, candyass bosses usually two decades his

junior, he realized that.

As the money ran low, and his friends stopped their loans, and the

police looked at him more closely the more his clothes began to fade, he

realized that.

The moon had other plans.

Another winter, and a third luckily mild. But the fourth was spent

freezing to death in an overcrowded shelter for homeless men in New York

City. Humiliation compounded when he was interviewed by a bleeding-heart

摘要:

展开>>

收起<<

THEPETCHARLESL.GRANTi"Anexcitingandwell-writtenhorrorstory....Abrilliantandfurioustale...asskillfulasthewhisperofthesurgeon'sblade."-WhitleyStrieber,authorofCatmagicThewaterlyingonthesaggingbrickwalkwasclearandunrippled,andalongoneedgewasashadowthatwasneitherthetreeintheyardnortheeavesnorhimselfcros...

声明:本站为文档C2C交易模式,即用户上传的文档直接被用户下载,本站只是中间服务平台,本站所有文档下载所得的收益归上传人(含作者)所有。玖贝云文库仅提供信息存储空间,仅对用户上传内容的表现方式做保护处理,对上载内容本身不做任何修改或编辑。若文档所含内容侵犯了您的版权或隐私,请立即通知玖贝云文库,我们立即给予删除!

分类:外语学习

价格:5.9玖币

属性:232 页

大小:473.73KB

格式:PDF

时间:2024-12-24

渝公网安备50010702506394

渝公网安备50010702506394