"But they might, and if they do, I want to go."

"It's impossible," he'd said. "Even if it were opened, Mediaeval wouldn't send a woman. An

unaccompanied woman was unheard of in the fourteenth century. Only women of the lowest class went

about alone, and they were fair game for any man or beast who happened along. Women of the

nobility and even the emerging middle class were constantly attended by their fathers or their

husbands or their servants, usually all three, and even if you weren't a woman, you're a student.

The fourteenth century is far too dangerous for Mediaeval to consider sending a student. They

would send an experienced historian."

"It's no more dangerous than Twentieth Century," Kivrin had said. "Mustard gas and automobile

crashes and pinpoints. At least no one's going to drop a bomb on me. And who's an experienced

Mediaeval historian? Nobody has on-site experience, and your Twentieth Century historians here at

Balliol don't know anything about the Middle Ages. Nobody knows anything. There are scarcely any

records, except for parish registers and tax rolls, and nobody knows what their lives were like at

all. That's why I want to go. I want to find out about them, how they lived, what they were

like. Won't you please help me?"

He had finally said, "I'm afraid you'll have to speak with Mediaeval about that," but it was too

late.

"I've already talked to them," she said. "They don't know anything about the Middle Ages either.

I mean, anything practical. Mr. Latimer's teaching me Middle English, but it's all pronomial

inflections and vowel shifts. He hasn't taught me to say anything.

"I need to know the language and the customs," she said, leaning over Dunworthy's desk, "and the

money and table manners and things. Did you know they didn't use plates? They used flat loaves

of bread called manchets, and when they finished eating their meat, they broke them into pieces

and ate them. I need someone to teach me things like that, so I won't make mistakes."

"I'm a twentieth-century historian, not a mediaevalist. I haven't studied the Middle Ages in

forty years."

"But you know the sorts of things I need to know. I can look them up and learn them, if you'll

just tell me what they are."

"What about Gilchrist?" he had said, even though he considered Gilchrist a self-important fool.

"He's working on the re-ranking and hasn't any time."

And what good will the re-ranking do if he has no historians to send? Dunworthy thought. "What

about Montoya? She's working on a mediaeval dig out near Witney, isn't she? She should know

something about the customs."

"Ms. Montoya hasn't any time either, she's so busy trying to recruit people to work on the

Skendgate dig. Don't you see? They're all useless. You're the only one who can help me."

He should have said, "Nevertheless, they are members of Brasenose's faculty, and I am not," but

instead he had been maliciously delighted to hear her tell him what he had thought all along, that

Latimer was a doddering old man and Montoya a frustrated archaeologist, that Gilchrist was

incapable of training historians. He had been eager to use her to show Mediaeval how it should be

done.

"We'll have you augmented with an interpreter," he had said. "And I want you to learn Church

Latin, Norman French, and Old German, in addition to Mr. Latimer's Middle English," and she had

immediately pulled a pencil and an exercise book from her pocket and begun making a list.

"You'll need practical experience in farming-milking a cow, gathering eggs, vegetable gardening,"

he'd said, ticking them off on his fingers. "Your hair isn't long enough. You'll need to take

cortixidils. You'll need to learn to spin, with a spindle, not a spinning wheel. The spinning

wheel wasn't invented yet. And you'll need to learn to ride a horse."

He had stopped, finally coming to his senses. "Do you know what you need to learn?" he had said,

watching her, earnestly bent over the list she was scribbling, her braids dangling over her

shoulders. "How to treat open sores and infected wounds, how to prepare a child's body for

burial, how to dig a grave. The mortality rate will still be worth a ten, even if Gilchrist

somehow succeeds in getting the ranking changed. The average life expectancy in 1300 was thirty-

eight. You have no business going there."

Kivrin had looked up, her pencil poised above the paper. "Where should I go to look at dead

bodies?" she had said earnestly. "The morgue? Or should I ask Dr. Ahrens in Infirmary?"

"I told her she couldn't go," Dunworthy said, still staring unseeing at the glass, "but she

wouldn't listen."

"I know," Mary said. "She wouldn't listen to me either."

Dunworthy sat down stiffly next to her. The rain and all that chasing after Basingame had

aggravated his arthritis. He still had his overcoat on. He struggled out of it and unwound the

muffler from around his neck.

file:///F|/rah/Connie%20Willis/Doomsday%20Book.txt (4 of 260) [1/17/03 2:31:34 AM]

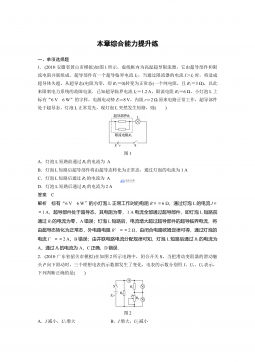

2024-12-12 94

2024-12-12 94

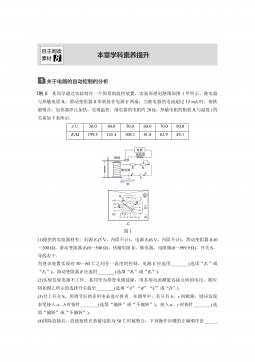

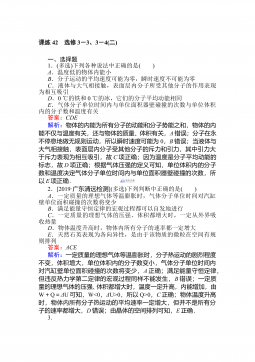

2025-03-17 7

2025-03-17 7

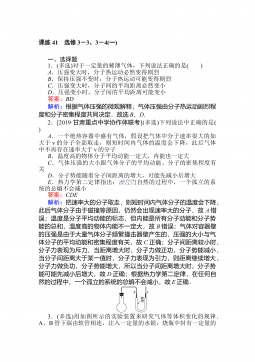

2025-03-17 9

2025-03-17 9

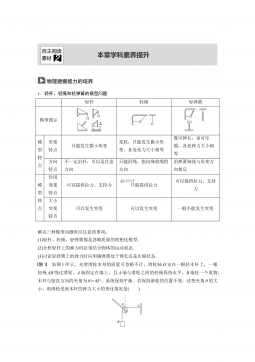

2025-03-17 8

2025-03-17 8

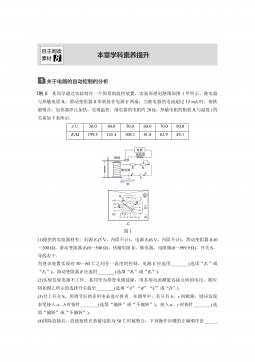

2025-03-17 4

2025-03-17 4

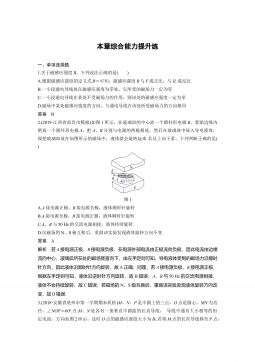

2025-03-17 9

2025-03-17 9

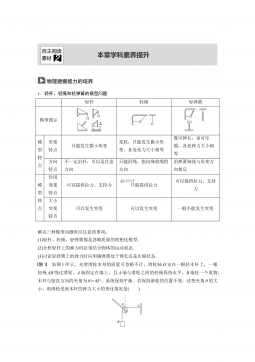

2025-03-17 8

2025-03-17 8

2025-03-17 12

2025-03-17 12

2025-03-17 12

2025-03-17 12

2025-03-17 11

2025-03-17 11

渝公网安备50010702506394

渝公网安备50010702506394